Explore our detailed review of YOASOBI’s latest album, The Book 3. Discover how Ayase’s masterful production and Ikura’s emotive vocals continue to redefine J-Pop with stunning storytelling and captivating melodies.

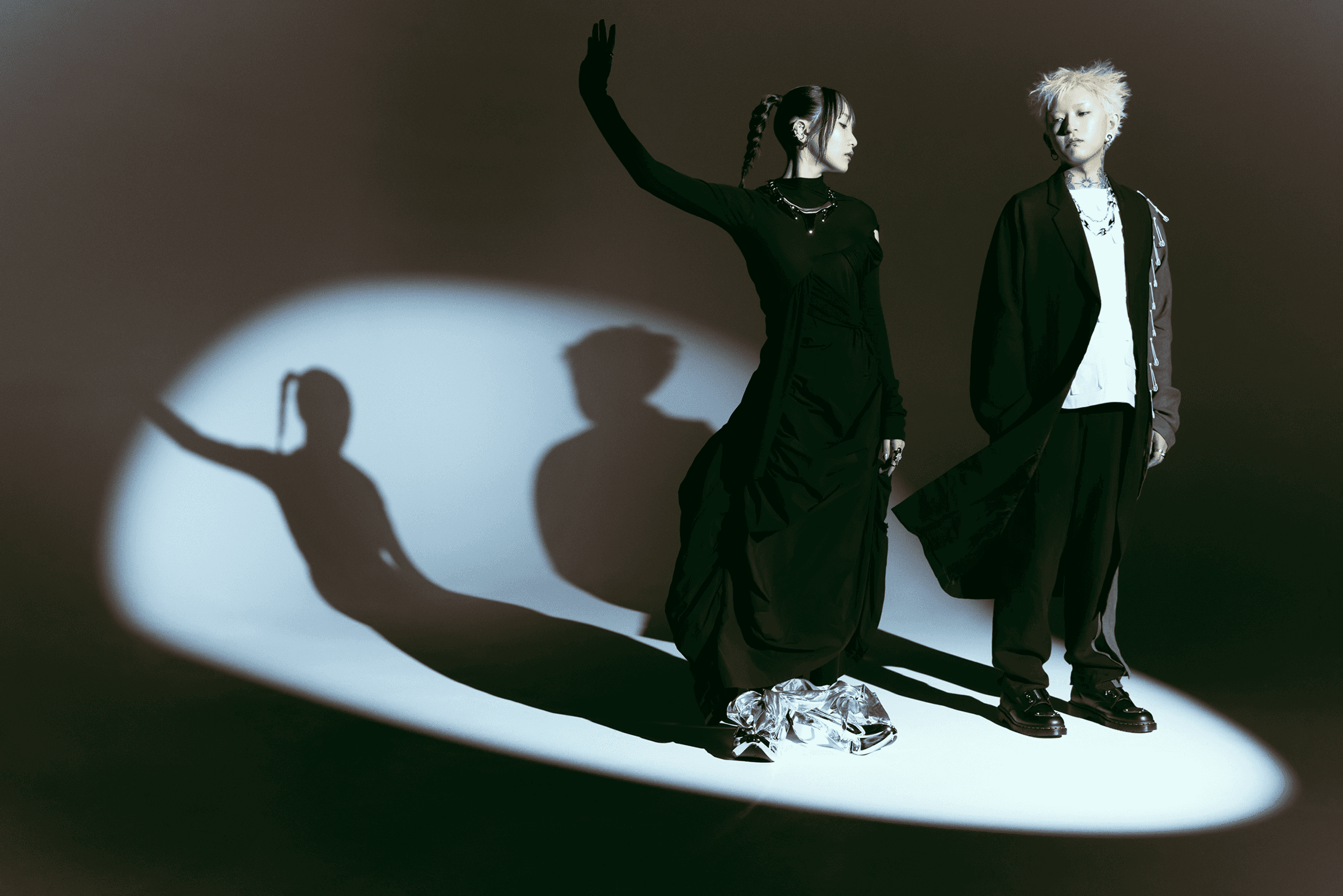

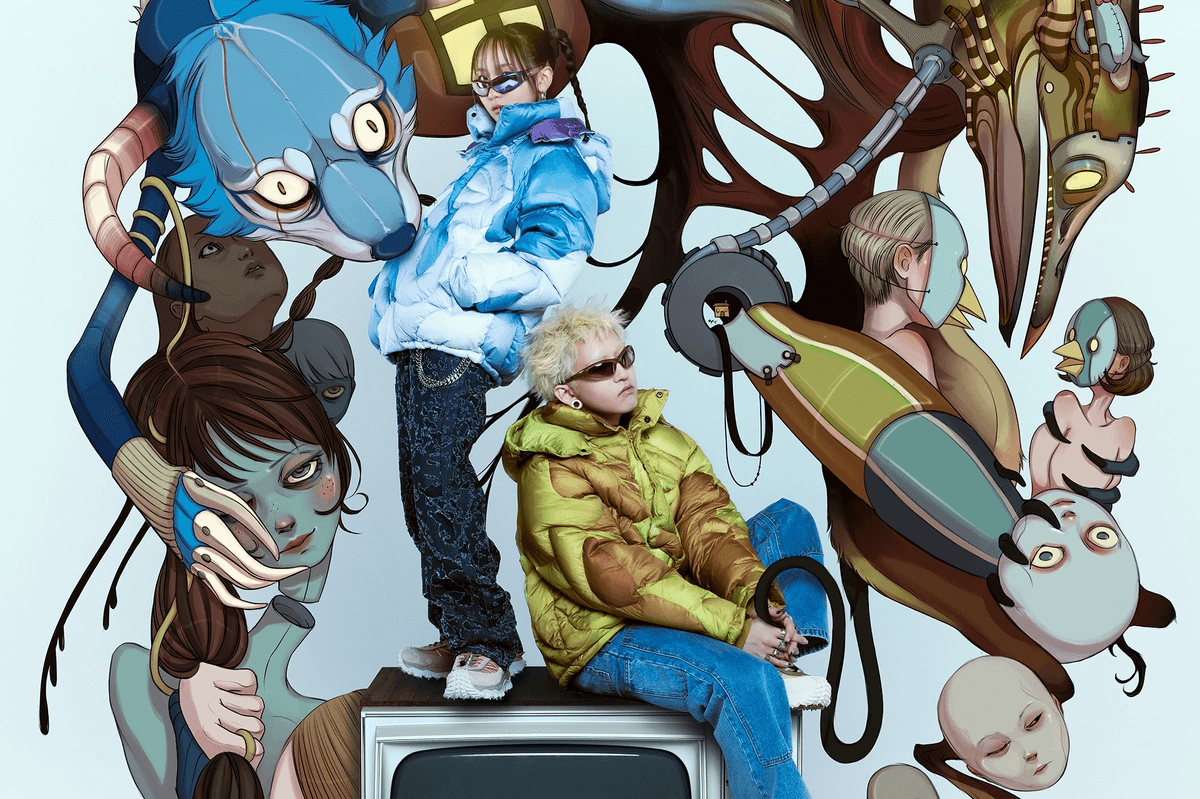

For a group that thrives on transforming written stories into songs, Yoasobi’s presence speaks volumes: Ayase, bold with his bleach-blonde hair and tattooed shoulders, embodies a quiet but commanding energy, while ikura, cloaked in a muted hoodie and silver face mask, exudes a reserved warmth. Their demeanor suggests exhaustion, but also the exhilaration of a group living through a transformative period. In April alone, we saw YOASOBI accomplish what many J-pop artists only dream of: performing at Coachella, headlining shows in the United States, and even visiting the White House—a nod to their growing cultural resonance. But how did this duo, formed from an experimental concept in 2019, grow to become ambassadors of Japanese pop culture on a global stage? To understand YOASOBI is to dive into their unique artistic philosophy: music as a vessel for storytelling.

YOASOBI’s origin is almost serendipitous. Ayase, bedridden with a peptic ulcer in 2018, found solace in producing Vocaloid music. This period of stillness birthed a spark of creativity that would later align with Sony Music Japan's Monogatary.com—an online platform for user-submitted short stories. The concept: adapt these narratives into music. Ayase scouted ikura, then an emerging artist with a modest but promising presence on social media. Their debut single, "Yoru ni Kakeru" (Into the Night), encapsulated this idea: a melody interwoven with the threads of the Monocon-winning short story Thanatos no Yuwaka. The song’s viral success in 2020—catapulted by the introspective and isolating backdrop of a global pandemic—was not just a breakout moment; it was a testament to the universal language of emotion and narrative. Yet, this was merely the prologue to their story.

At its core, YOASOBI’s music is a study in contrasts: simplicity of concept juxtaposed with maximalist execution. Their songs are structurally tethered to their literary roots, and yet they expand beyond the confines of text through Ayase's intricate compositions and ikura’s evocative delivery. In a world increasingly fractured by niche interests, YOASOBI's ability to span media—from novels to anime to global pop stages—feels almost revolutionary. Whether it's their Blue Period-inspired track "Gunjo" (Blue), the Beastarsopening "Kaibutsu" (Monster), or the addictive Oshi no Ko theme "Idol", the duo thrives on the synergy between narrative and melody. Ayase reflects on the creative process as one of immersion. "Every song begins with the story," he explains. "It’s about distilling its essence and then finding the coolest way to translate that into music," they mentioned in a recent interview. But there’s also an interplay between art and commerce. Collaborating with established media properties introduces YOASOBI to audiences who might otherwise miss their literary-inspired work. Is this purely strategic, or does it speak to something more intrinsic about how we consume art in the digital age?

With the release of their English EPs—the E-Side series—YOASOBI has made deliberate strides toward international accessibility. These adaptations are not mere translations but reinterpretations, with lyricist Konnie Aoki painstakingly preserving the poetic cadence of the original Japanese while allowing the music to resonate with a broader audience. Their performance at Coachella, where the desert heat met their effervescent beats, was both a milestone and a moment of reflection. Ikura observes, “It feels surreal to see our songs cross borders and languages, but it’s also a reminder of how much further we can go.” This global pivot raises an interesting question: How does a group rooted in the nuances of Japanese storytelling maintain its cultural authenticity while adapting to an increasingly globalized world?